Dos Motos in Patagonia

by Bob Stokstad

"Man, the measure of all things, speaks through my mouth and recounts in my own words what my eyes have seen." Ernesto Che Guevara, in The Motorcycle Diaries

"Patagonia" sounds remote and wild, a place to go only for a good reason and with a lot of time. The late Bruce Chatwin, author of the captivating travelog "In Patagonia" had both reason and time. For six solitary months he followed in the first footsteps of the early settlers and last ones of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. So do the long-haul adventure riders, who head for Ushuaia at the bottom of Tierra del Fuego, the holy grail of motorcycling, where the road ends. But there's more to Patagonia than the end of the road. This vast region of South America, with its beauty, rugged terrain, and contrasting climates offers adventure even for the dual-sport rider with limited time. How much and what kind of adventure? That's the question my friend, Torsten Jacobsen, and I set out to answer in January 2008 when we rented motorcycles in Argentina and headed for the Andes with a map and a maximum two weeks to burn on the road. We planned to cross the continental divide near San Carlos de Bariloche and ride south in Chile, on the wetter, lush side of the Andes. At some later date we would turn eastward, cross the Andes again and head back north in Argentina on Ruta 40, closing the loop near Bariloche.

|

The bright sun at our backs on the morning of January 17, we left Neuquen, a city in southwestern Argentina, to see Patagonia. 180 kilometers down the road Torsten had his first flat tire. Not an auspicious beginning for our trip, I thought, but once we get the Honda Transalp up on the center stand, tire off, new tube in, we'll be fine. Center stand? Not on this bike. An assortment of football sized rocks from the side of the road will substitute for a center stand, however, and you don't have to take the rocks with you after the tire's fixed. An hour later we were back in business.

The western part of Argentina has much in common with our own West. At times, it seemed, we could have been riding in parts of Nevada or Utah - with one big difference. There aren't nearly as many buildings, people, or cars here. Along with sheer size, it is this absence that defines Patagonian remoteness. Our first day was exhilarating, beginning with straight roads in dry range land, then broad sweepers following rivers up into the forested foothills of the mountains. San Martin des los Andes, where we stopped for the night, is a small, picturesque alpine town with stone-and-log buildings and a ski-lodge atmosphere. Still, these weren't reasons enough to come half way around the world.

|

On a map, the southern part of Chile resembles a spine. The north-south ridge of the Andes forms a continuous column, while the costal peninsulas appear as vertebrae interrupting the ocean to form fjords. This topography means at least one major ferry crossing in any itinerary. If you are driving a car, a reservation this time of year is essential. But there's always room for a motorcycle. Right? Arriving several hours before the scheduled ferry departure from Hornopiren, we walked into the office, a converted shipping container, and tried to buy tickets. "I'm sorry, the ferry is fully-booked for the next two days," was the response from the sweet young couple behind the desk. We began the song and dance from that Broadway hit "There's always room for a motorcycle" and, for an encore, Torsten offered up an extra $20 bill for each of them, just to show our appreciation. A few minutes later the young man was outside writing down our license plate numbers for the vehicle tickets. Our passenger tickets would be dated for tomorrow, he said, because the ferry wasn't supposed to have more than 80 people on it. Whatever.

|

We left our motorcycles, strapped to the deck like Gulliver in Lilliput, to scout the ferry for a sheltered spot in the afternoon sun and out of the wind. Between the ferry and the winding coast the water became a million tiny mirrors, seen only by us passengers and our escort of shorebirds and a few tireless dolphins. After six hours and as many granola bars, the ferry's hinged steel bow clanked onto a primitive ramp at the end of a gravel road leading into the jungle. The sun was low, and we still had 80 kilometers to ride on this two-track, curve-filled, high-crowned road in Parque Pumalin before coming to Chaiten where, Torsten's copy of The Lonely Planet told us, we could eat well and sleep for not a lot of money.

Parque Pumalin, one of the largest parks in Chile, was established by North American clothing magnate and environmental philanthropist Douglas Tompkins (founder of The North Face and Espirit) who bought up the land to protect this temperate rain forest from commercial exploitation. Incredibly rich in wildlife, plants, lakes and waterfalls, it is only sparsely developed with campsites and hiking trails. We stayed another day just to explore the park, now with time to walk some of the trails. A rain in the afternoon cut short our hike and we turned back to Chaiten, at which point the heavens opened and made a major contribution to the area's 6000 millimeter annual rainfall.

|

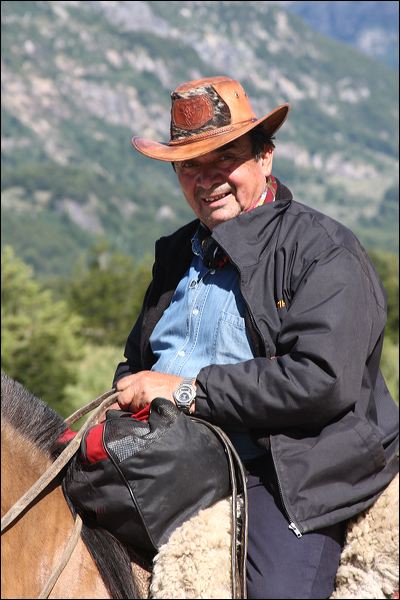

Our introduction to Chile was eye-opening - fertile farms and pastureland with snow-capped volcanic cones looming in the distance, mountains covered by lush green vegetation up to the snow line, and pristine lakes. But this was only a teaser for what awaited us on our ride south along Ruta 7, the Carretera Austral. Since our map indicated over 400 kilometers of mostly gravel road between Chaiten and Coihaique, we didn't plan to go this whole distance in one day. Nor was the morning rain encouraging. But at midday the sun reappeared and what we began to see made it impossible to stop. It was picture-book Patagonia. Imagine taking elements of our own Sierra, Grand Teton, Denali and Glacier National parks and assembling a collage from the most scenic parts of each -- that approaches the majestic grandeur of Chilean Patagonia. There was, at times, a wide river, then narrow whitewater rapids, lakes mirroring mountain peaks, a small farm house with a hanging glacier as a backdrop, windswept poplar trees, and a gaucho on horseback with a herd dog running along side. It was late when we arrived in Coihaique, but this day was reason enough for the journey to South America.

Our goal now became Chile Chico on the southern shore of Lake General Carrera, a giant blue body of water that straddles the Argentina - Chile border. Two days of dusty gravel roads through majestic scenery lay between Coihaique and this decision point where we would then go north either by backtracking Carretera Austral in Chile or by returning to Argentina and tackling Ruta 40.

|

A 5000 kilometers long north-south highway running nearly the entire length of Argentina, Ruta 40 is legendary for punishing people and machines with 100 km/h cross winds, deep gravel, and butt-numbing dirt washboards on its unpaved southern sections. We would join it somewhere in the middle and were initially uncertain about what we would encounter. By the time we reached Chile Chico we had learned from other motorcyclists that our 900 kilometers stretch on Ruta 40 involved only 115 kilometers of gravel. Picture a four-lane section of California freeway ready for paving. Instead, strew it with gravel and punctuate it with occasional potholes and washboards: this is the section of Ruta 40 between the towns of Perito Moreno and Rio Mayo. The ferocious Patagonian wind, which might have made the ride more exciting, was absent. The main challenge was keeping our speed under 100 km/h because potholes have a way of sneaking up and bending a wheel rim when you least expect it. The tough stretches of Ruta 40 must lie farther to the south, on the way to Ushuaia.

Once past Chile Chico, our mountain paradise of the last week had reverted to open range on the parched eastern side of the Andes. Dry, yes, but not empty - we saw handsome horses, a herd of llamas and, Torsten swears, a few emus wandering among the scrub bushes carpeting the desert floor. Scenic relief came later in the day in the form of infinite puffy white clouds floating in a deep blue sky. We pushed on and made it to Trevelin, a small town in the Andean foothills.

|

In the 1800's settlers from Wales arrived in the provence of Chubut to find a place of refuge from a dominating English culture. Today, there are 500,000 inhabitants of this vast chunk of Argentina, which stretches from the Andes to the Atlantic, and 50,000 of them speak Welsh. "Trevelin," which combines the Welsh words for town and mill, was the home of John Evans, a miller whose descendents still live here. This area also was temporary refuge for the north american outlaws Robert LeRoy Parker and Harry Longabaugh, aka Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, who were fleeing the relentless Pinkertons. At the Evans homestead, John Evan's granddaughter Clery Evans explained to us how her father spent days telling a young solitary traveler, Bruce Chatwin, about Welsh history in Chubut and the local stories of Cassidy and the Kid. Chatwin's description of Patagonia was first published in 1977 and is worth reading even if Patagonia isn't the next place you plan to visit.

|

North of Trevelin is the national park "Los Alerces." The alerce tree resembles our sequoia in size and are the oldest trees on earth after the bristlecone pines. Seventy kilometers of gravel road and a one-mile hike to a mountain-ringed lake brought us to the start of a day cruise to a giant grove of alerces. The boat ride and hike showed us of how much Argentines appreciate their natural heritage. Torsten and I, the only gringos on the boat, were welcomed by the other passengers and the boat's crew, who seemed fascinated that the Dos Hombres chose Dos Motos to explore Patagonia.

Only 35 kilometers from the Chilean border, Trevelin is also the eastern gateway to Futaleufu - the town and the river. The latter, now famous for its white water, was first kayacked in the '80s by an American, Chris Spelius. Now there are four american-run companies in Futaleufu (and an equalnumber of local rafting companies) that cater largely to North Americans and Europeans who fly here just for the kayacking and rafting. The yanquis are welcomed by the locals (Spelius has a Chilean wife) and the town's atmosphere has not suffered from their presence. We hung out on the deck of the main hotel in town for a while, where Torsten learned from the ambient rafting crowd that we could get spots on a raft the next day.

|

Next morning we sat in the spanish-speaking raft and rode the rapids, learning new commands with a value extending well beyond rafting. like "Aliante fuerte - muoy fuerte," which means "paddle like hell." Rapids with names like Terminator, Kyber Pass, or Inferno came, one after another, links in a seemingly endless chain. Before entering a rapid, we were instructed whether to swim to the right bank or left bank in case of a flip. It's easy to understand why this river is so prized by the world-wide rafting community, which hopes they can enjoy the Futalfeu for perhaps another ten years before a hydroelectric dam puts an end to the white water. There is a movement in Chile to protect the wild rivers and scenic heritage. It's called "Patagonia sin Represas" - Patagonia Without Dams - and its literature is prominent. But, sadly, we encountered little optimism that it would prevail.

Back across the border into Argentina after two nights in Futaleufu, we headed up Ruta 40 to San Carlos de Bariloche, Argentina's famous ski-resort and vacation magnet. On this day, Torsten had his third flat. Stones for propping up the bike were hard to find at this spot, and the two spare rear tubes had been destroyed previously when the valve stem was ripped out by the tire slipping on the rim. I'd patched the tube that had survived the first flat, however, and in it went. Now we had no spares at all, and another ripped valve stem would put us out of business. We kept our speed under fifty.

|

Bariloche is located on a lake in a stunning part of the Andes. One might argue that it is overdeveloped - but there's no doubt it is overcrowded at this time of year. While I motored out to see the countryside, Torsten devoted his day to finding spare tubes. He located a motorcycle tire store, only to learn that the proprietor had sold ALL his 17" rear tubes that morning. Always a quick study, Torsten got the name and phone number of the buyer. By the end of the day, he'd tracked down the person who'd cornered the Bariloche tube market and was able to score two spares. With these, we wouldn't be stranded by the side of the road on our last day if Torsten's bad tire karma were to continue.

|

The ride to Neuquen, where that evening we would return our now-beloved Transalps, was a high point in the morning as we rode along Rio Limay, stopping frequently to view the river as it carved its way east. The town of Piedra del Aguila, the halfway gas stop between Bariloche and Neuquen, also marks the transition from Andean landscape to flat plain. Fifty six years ago, to the day, two other motorcyclists also arrived in Piedra del Aquila. They were on foot, carrying a broken piece of their Norton 500, and looking for a welder. Che Guevara and Alberto Granado were on their epic journey to North America, riding roads (some of them still gravel!) that we traveled in the space of two weeks. Their journey was high adventure. Was ours? The answer doesn't really matter - we'd had a fantastic trip of over 3600 kilometers in a Patagonian paradise, enjoying the places and the people, and even 1600 kilometers of gravel roads without once dropping a bike. After a half hour of sweating in the afternoon heat and traffic, looking for a cheap hotel in Neuquen, we sat down at a sidewalk bar. I raised my glass to Torsten and the Transalps. Tomorrow we'd spend eighteen hours in three airplanes before landing in San Francisco. This evening we were in heaven.